Richard Cork’s introductory essay for the exhibition Lines of Flight at Marlborough Fine Art, 2006.

- Speechless, 2005

- Scanner, 2005

- Light (vertical), 2005

- Insomnia, 2005

As soon as we encounter Thérèse Oulton’s work, the dramatic instability of her vision becomes impossible to ignore. At one instant, a monumental land-mass seems to spread across the canvas, impregnable and reassuring. Then, quite suddenly, it trembles on the verge of dissolution. The apparently solid elements within the painting break apart, making us aware of its fundamental vulnerability. Oulton appears to hover between two worlds, like an insomniac who feels that her mind is half awake, half dreaming.

By a paradox, though, she turns this perpetual oscillation into a source of immense strength. If Oulton can be situated within any painting tradition at all, the landscape genre seems closest to her essential concerns. But there is no question of her taking up a single, static vantage in the countryside and scrutinising one particular location. When she mounted her first solo exhibition at Gimpel Fils back in 1984, Oulton revealed a fascination with the romantic notion of the sublime. Even then, however, she distanced herself from an unqualified involvement. The show was called Fool’s Gold, as if to emphasize her own loss of faith. And I realised, when writing about these early paintings, that the idea of landscape had already given way to a boundless sense of space, where “much of the drama arose from the spectacle created by skeins of paint flung into a void.”

By the time Oulton held her debut exhibition at Marlborough Fine Art four years later, she had developed a greater degree of solidity by stiffening her work with encrusted pigment and a greater reliance on structural rigour. The paintings seemed flatter and thicker than before, yet Oulton never aimed at stressing textural density at the expense of other, more nebulous possibilities. Tantalisingly dream-like vistas could still be glimpsed beneath the craggy paint-deposits, and she did not seek to hide the tension between these conflicting visions.

- Apparition, 2003

- Apparition, 2003

Nor did she shy away from disclosing, through her work, that landscape references were metaphors for her own states of mind. The same overall priority governs the work in her new exhibition as well. Among the earliest paintings on view here are two elusive images called, intriguingly, Apparition. Their surfaces are scattered with fragments handled in such a broken, richly textured way that we feel tempted to reach out and grasp them. But they cannot be pinned down. Although the space they occupy seems to recede, Oulton dapples it with slender light-patches that reassert the flatness of the canvas. Our attempt to locate the precise position of the fragments is thwarted, even if they all appear to cast shadows on the emptiness beneath them.

No wonder she gives both these images such ghostly names. They haunt us like persistent nightmares refusing to yield all their secrets, and Oulton is never afraid of invading the undoubted lyricism in her work with abrupt, alarming violence. Surplus is, for the most part, awash with pale, swirling brushmarks redolent of sea or sky. Across the centre, however, a clotted mass of darker, more ominous particles disrupts the equilibrium. They belong to a harsher, more assertive order, and the title Surplus implies that they could be in danger of overloading the precarious balance maintained elsewhere.

- Surplus, 2003

- Bare Bones, 2003

- White Lies, 2004

They may, however, have a more positive role. If Oulton is fascinated by disintegration, she is also alive to the possibility of survival. So Surplus might equally well celebrate the defiant build-up of cellular matter tough enough to withstand destruction. And a similar duality informs a larger painting called Bare Bones, even if its title calls attention to mortality in the most overt manner imaginable. Within a space animated by the restless motion of soft and luminous elements, harder forms float like obstinate remains of bodies long since consigned to the grave. Although Oulton is an abstract artist and avoids clearly identifiable references, the suggestion of a hand can be detected near the centre. It reminds us that bones live on long after the rest of a body succumbs to decomposition. So there is a hint of defiance about this hand, despite the disintegration evident all around.

During the period encompassed by this exhibition, Oulton’s mother died after a slow decline. On one level, Bare Bones may therefore be impelled by a painfully autobiographical sense of urgency. But it could be concerned with art as well as mortality. As Oulton’s work attests, she is fascinated by the bare bones of painting. And the stubborn survival of the hand could stand as a metaphor for the art-work’s ability to outlast the limited lifespan of its maker.

By calling another of her canvasses White Lies, Oulton implies that art thrives on free-floating invention rather than any supposed fidelity to verifiable facts. The world of appearance is undermined at every turn, and in White Lies we are left with a glistening essence. Avoiding all the descriptive and narrative baggage that once attached itself to painting, she relishes its seductiveness. White Lies is irresistably beguiling, and invites us to roam as far as our minds will stretch.

At the same time, though, Oulton never lets us forget how little we can really know. Camera Obscura‘s title might seem to refer solely to the ingenious optical instrument which gives viewers such a remarkably comprehensive picture of the surrounding world. The painting itself quickly disabuses us of such a notion, though. The darker half does appear to open out into a universe where vast distances are indicated. But it is a dizzying space filled with suggestions rather than definable facts, and the other half of the picture is covered with a palpable mist bent on frustrating our ability to discern everything beyond.

Even when she calls one of her images Infrared, we cannot discover the kind of visual information which such a name might lead us to expect. As an investigative device, infra-red is relied on to impart valuable and otherwise indetectable information about the world below the surface of things. Oulton, by contrast, offers disclosures of a very different kind. Everything is embroiled in a state of flux throughout this painting. Even the least tumultuous areas are threatened by imminent disturbance. It is as if an explosion has occurred along the centre of the canvas, flinging fragments towards all four edges. Some of the most textured forms resemble the hand in Bare Bones, but they are no longer whole. Each particle seems to be splintering, and thereby losing whatever semblance of identity it once possessed.

Storms now appear to have invaded Oulton’s art, and they prove still more disruptive in a painting entitled Panorama. The spectacle promised by the name is contradicted by the image itself. Far from providing an epic sweep of uninterrupted vision, Panorama is riddled with broken particles. Some kind of cataclysm has occured, smashing every object in its path and hurling them all outwards. They spin helplessly in a region redolent of the cosmos rather than planet Earth. So maybe this convulsive event is occurring in deep space, among the stars. Oulton must surely find stimulus in the images discovered by the most advanced astronomical exploration.

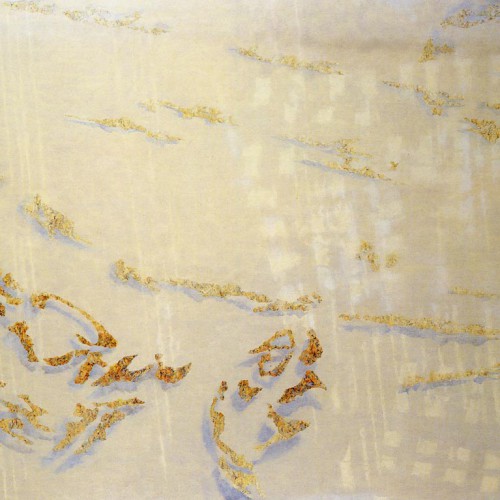

Even at her most demonstrative, however, she never resorts to excitable brushmarks or thick, heaped pigment. Oulton abhors the whole notion of heavily layered pictures, where the paint has been piled on or glazed so obtrusively that a tired air of seamlessness results. She always handles her materials thinly and without emphatic gesturing. Ideally, Oulton would like to make viewers more aware of the bare canvas beneath, just as Cézanne did in his late work. But she cannot resist covering most of her picture with pigment, and in a painting as eventful as Scanner an abundance of leaf-like forms fly across almost every area of the work’s surface. The shimmering outcome suggests a desire, on Oulton’s part, to vie with the shiny luminosity of the screens where scanning normally occurs.

Most of the time, though, she avoids such all-over consistency and opts instead for a more galvanic tension between opposing forces within each picture. Insomnia, one of the most haunting images Oulton has ever produced, confronts a pallid land-mass of continental proportions with a thin expanse of dense black at the painting’s base. It looks almost glacial, and on the point of engulfment by the nocturnal paint menacing its lower edge.

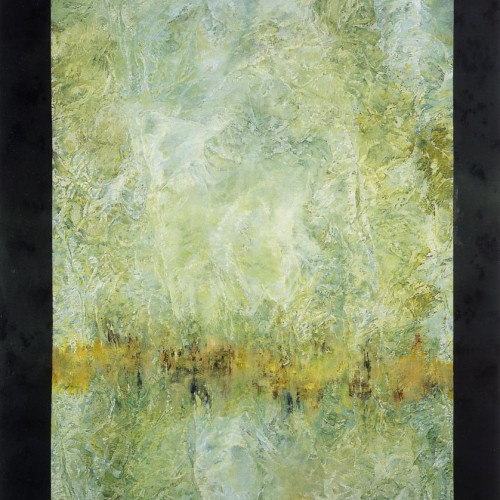

A related sense of menace runs through Speechless as well. Bordered on both flanks by funeral strips of dark pigment, it is filled largely with pale green-grey pigment reminiscent of a mountainous region swathed in snow. Stretching across the icy terrain is a warmer, strangely autumnal fissure. It threatens to crack open the rest of the picture, helping to explain why Oulton gave this work such an ominous title.

While executing Speechless, she became unaccountably convinced that her own career was approaching a premature end. Artists are no strangers to self-doubt, so Oulton is far from alone in becoming preoccupied with the sense of an ending. Thoughts about death may well have helped engender this mood, and in a couple of paintings called Ghost Trio she explores the possibility that everything is in danger of succumbing to a mysterious spectral melt-down.

But the truth is that Oulton’s work has never been more eloquent than it is today. Far from fading into terminal silence, she continues to produce images quickened by a poetic understanding of life at its most complex and unpredictable. Although she may occasionally feel tempted by the urge to escape, Oulton’s attentiveness to every nuance of experience remains unshaken. Working in a small, dark studio in West London, where the unexpected advent of the sun can hit the room like a revelation, she is able to convey its primal force in two small paintings simply called Light. They sum up her transforming ability to convey the vital essence of things with subtlety, resourcefulness and verve.

Four paperbacks of Richard Cork’s writings on modern art, including Thérèse Oulton’s earlier work, are published by Yale.