Jacqueline Rose’s catalogue essay for Elsewhere, Marlborough Fine Art, London 2014.

- Coastline, 2011

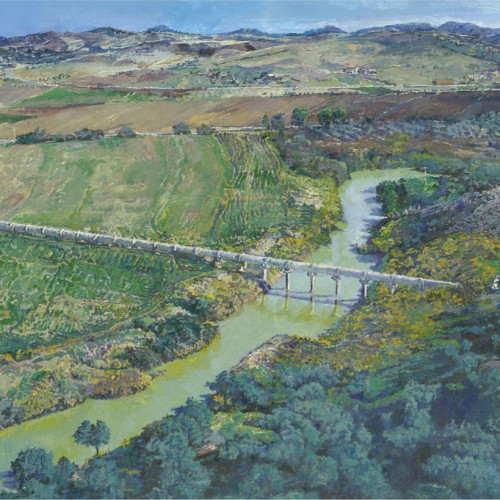

- Pipeline, 2011

- Rock Face, 2014

- Terminal Moraine, 2013-14

What does it mean to imagine the world destroyed? The proposition makes no sense since, if the world has been destroyed, there would be no one left to imagine it.

This is why disaster movies like I Am Legend or even novels like Cormac McCarthy’s The Road are so misleading or even comforting. Someone, however precariously, always survives, as well as the spectator or reader who is watching. How, then, to represent a world on the verge of extinction, or one which has extinction already written across its surface? How or where should you place the viewer of a vanishing world? How to paint the earth lovingly but without false solace, a world in which love might be impotent?

Since her 2010 exhibition, Territory, Thérèse Oulton has been quietly painting herself into the heart of these questions. Not for the first time, she places us in the realm of something which is almost impossible to envisage. As with all Oulton’s work, the paintings of Elsewhere, this new exhibition, are disarmingly exquisite, but they do not pretend to redeem man’s destructiveness. This dilemma requires new forms. It calls for what Rosa Luxemburg once described as ‘a new guest… the human being’ – she was writing with reference to a devastating volcanic eruption in 1902 on the island of Martinique.1 Oulton, we might say, is creating a new viewer, one who has to look in two self-contradictory, or self-annihilating directions at once. First she brings your face right up to the world’s surface, closer probably than you have ever experienced it before. But then, at the very moment you have ceded such intimacy, she manages to give you the sensation of a world hurtling to the point when there might no longer be anything, or anybody, there.

‘Suppose’, Oulton has recently suggested, ‘we are witnessing a whole form of life collapsing, ceasing to exist as the determinant form of the human?’2 The paintings of Elsewhere demand a peculiar type of ‘inhuman proximity’ – from artist and viewer alike. ‘Does the space of belonging’, she asks, ‘survive at all?’3 According to scientific commentator, Elizabeth Kolbert, we have entered the epoch of the ‘sixth extinction’ – the most devastation of the first five took place some 250 million years ago and almost emptied out the earth altogether (it is known as the ‘mother of mass extinctions’ or the ‘great dying’.)4 This time around, Kolbert writes, the extinction is of our own making. The cataclysm, as she puts it, ‘is us’.5

From the beginning of her career, Oulton’s immovable commitment has been to paint as matter. Today, the world as matter – what we have done to it, whether we can survive its depredations – is the burning issue. We could say that the world has finally caught up with her (although one suspects this would be cold comfort). For Oulton this has always been a political question. Oulton has never fully belonged inside the landscape tradition which might seem her most obvious affiliation. As early as 1987, she explained her distance in terms of a control she was not interested in exerting. The problem was how landscape is ‘appropriated both in the real world and in the painted landscape.’6 ‘I see it’, she continued, ‘as a kind of parallel – finding a way of approaching the subject of paint. Treating it less brutally.’7

She was way ahead of herself (and indeed most of us), although the continuities between the almost overwhelming lushness and density of the earlier work – from Fools’ Gold of 1984 to Lines of Flight of 2003-2005 – and the painstakingly detailed recording of a disintegrating world in the later paintings are stronger than one might at first think. For me, Oulton has always been a painter of unique, uncompromising, sensuousness. I have always seen her a digging her nails into the rock faces, into the underground hollows and sludge of the earth (what landscape mostly chooses not to represent). This is the process of her art, as she herself has described it. Oulton slides her paint across the canvas, one skin deep, no one brush mark on top of another: ‘It’s only touched once’.8 The key aesthetic demand seems to be that of preventing each trace and gesture from being wiped out by the next. To that extent, hers has always been an aesthetic of care, a means, as she once put it, of ‘letting the whole take care of itself.’9

Today the stakes of such a commitment are higher. Once we recognise – although many still deny – the damage we have wrought on the earth, then everything starts to look different. The whole tradition of landscape painting, for instance, might seem like a defensive form of art: ‘Might the petrified fixity of a painted landscape be an effect of anxiety’, Oulton now asks, ‘to freeze this narrative moment towards catastrophe?’10 To look at these paintings is to register the anxiety and beauty in the same place. Pleasure becomes its own warning-signal, as if today, against the more familiar norms of aesthetic appreciation, pleasure could only be anxious, a form of experience permanently menaced by itself.

Seen in this light, there is something deceptive about the titles of these paintings – Glacier, Quarry, Headland, Rock Face and Ice – which might suggest the world is available to be classified and known. Oulton has always pitched herself against such over-arching presumption. In fact, all we are being given are the geographical feature – the sites have no place names and could be anywhere (thus always potentially elsewhere.) The overall effect of these paintings is one of vertigo and groundlessness, a world endlessly on the move. Such radical disorientation can be read as a type of political resistance in itself. As she put it in relation to Territory: ‘matter constantly shifting about, unfit to be the landscape of political control.’11 Even as the meticulous differentiation of the painted surface is also a way of holding on the swill and soil of the earth, insisting against all odds on its ‘thereness’ (her word).12

The paintings of Territory showed the world as scarred. Images, reduced in scale from the vast earlier canvases, picked out the microscopic details of the ravaged earth with a precision we had not seen in Oulton’s paintings before. This was another split injunction – we were being asked to focus minutely on something that was also vanishing before our eyes. The paintings of Elsewhere can be seen as her response to the anxiety of the predicament which it also intensifies. Something elemental has entered the paintings, which are mostly now larger in scale. Ice hits rock, glaciers seem to be moving across the canvas, as if nature were now miming the endless slide of Oulton’s paint. In Terminal Moraine, for example, we look at the canvas, the paint seems to be coagulating, thickening, each stroke, each element struggling to hold its ground and stay in its own place. The ice, swathes of white almost but not quite broken by miniscule variations of tone, and the earth, thick brown marks coiling into their own depths, appear to be – barely – holding out against each other. We see the same effect in Fissure and Glacier, where the ice seems to be packing itself against a darker mass that threatens at the far edge of the canvas. A concave shape at the lower right hand edge of Glacier, rents the surface, as though the ice, and the whole painting with it, is about to be sucked into a black hole. What we have done – Oulton shows us like no other painter today – is pitch the elements into an unending war.

A terminal moraine, I then discover, is the snout of a glacier marking its maximum advance. The dense brown at the base of the canvas is in fact the debris accumulated by plucking and abrasion which is then deposited in a heap by the glacier at the point where it can go no further – as if you could lay down your arms by dumping the shit of your enemy at his own feet. In Norway, there is a terminal moraine called ‘Giant’s Wall’ which, according to legend was built by giants to keep out invaders. Oulton is now placing herself on the other side of the sublime. Be awed by nature – so long as you recognise that today the awe arises less from nature’s magnificence than from the human capacity to destroy it.

Elsewhere, the title of the exhibition, has another meaning. It refers, more simply but no less disquietingly, to rootlessness as the condition of our times, to migrants, asylum seekers and refugees as the ghostly figures in our landscape. Writing on stateless people in the 1950s, Hannah Arendt described how a person deprived of citizenship is reduced to what she called the ‘dark background of mere difference’ – a realm in which ‘man cannot change and cannot act and in which, therefore, he has a distinct tendency to destroy.’13 Millions of people today are homeless, in flight from the ravages of wars (more than after the Second World War when Arendt was writing). Taken together as two forms of violence, assaults on the ground – in military terms – and on the body of the earth are of course profoundly linked, testament to the same conglomerates of power. In paintings of often stunning luminosity, Thérèse Oulton manages to paint us into the darkest spaces of our times, displaying once again her exceptional, on-going relevance, for anyone trying to understand them.

Jacqueline Rose writes more fully about Thérèse Oulton’s work in Women in Dark Times (Bloomsbury).

Rosa Luxemburg, ‘Martinique’, 1902, The Rosa Luxemburg Reader, ed. Peter Hudis and Kevin B. Anderson (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2004), p. 123. ↩

‘Notes’, Conversation with Jacqueline Rose, London, 15 May 2014. ↩

‘Notes’, Conversation with Jacqueline Rose, London, 15 May 2014. ↩

Elizabeth Kolbert, The Sixth Extinction – An Unnatural History (London: Bloomsbury, 2014), p.6. ↩

Kolbert, p.267 and jacket. ↩

‘Interview with Sarah Kent’, FlashArt, 127, April 1987, p. 43. ↩

‘Interview with Sarah Kent’, FlashArt, 127, April 1987, p. 43. My emphasis. ↩

‘Interview with Sarah Kent’, FlashArt, 127, April 1987, p. 41. ↩

‘Double Vision: Therese Oulton in conversation with Stuart Morgan’, Artscribe International, 69, May 1988, p.8. ↩

‘Notes’, Conversation with Jacqueline Rose, London, 15 May 2014. ↩

Thérèse Oulton, ‘Brief Notes on a Change of Identity’, Territory (London: Marlborough Fine Arts Publications, 2010, unnumbered. ↩

‘Notes’, Conversation with Jacqueline Rose, London, 15 May 2014. ↩

Hannah Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism, (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1979), p. 301-302. ↩